100 Years, 100 Stories – February

100 Years, 100 Stories

February: Island of Immigrants

Only the Wampanoag can legitimately claim to be the first people on Martha’s Vineyard. Everyone else is descended from English colonists who arrived in the 17th century, or from people who landed here in subsequent waves of immigrants, or came as families or individuals in search of a life better than the one they left behind. This immigration, and its enrichment of the Island’s culture, continues to this day.

1. Buying, selling, and taking

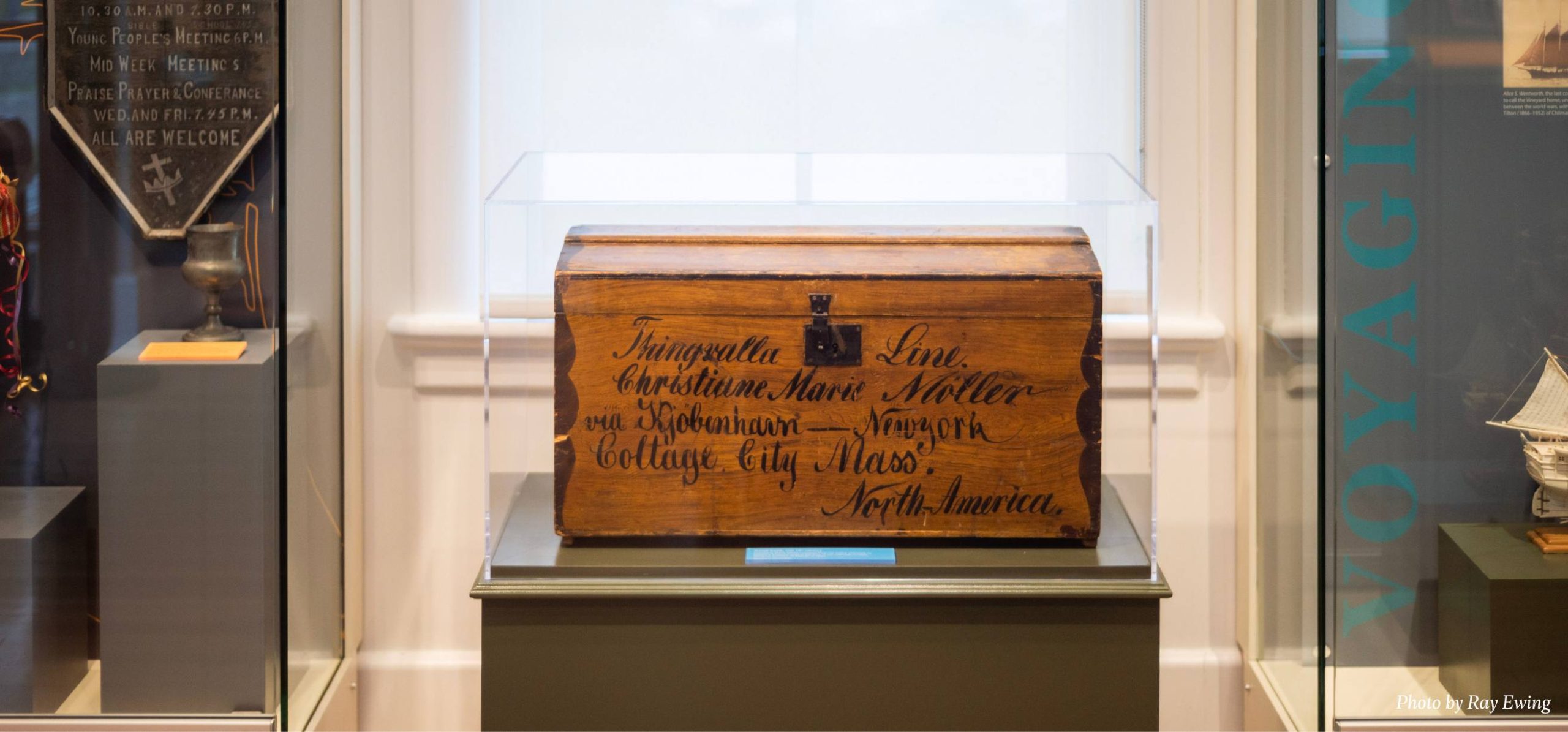

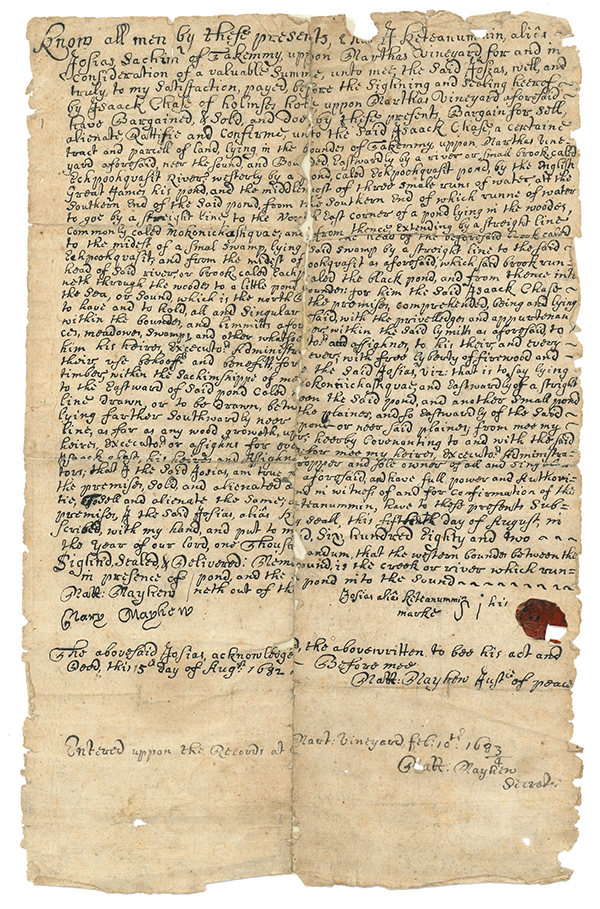

Title: Deed to Property in Takemmy

Date: 1682

Reference: RU132

Keteanummin (also known as Josias), Sachem of Takemmy, sold a portion of land in what is now Tisbury to Isaac Chase in 1682. It was not the first parcel he had sold to an English colonist. In 1664, Wampanoag tribal members protested to Thomas Mayhew that too much land was being transferred out of their control, forcing them to move away from areas that they had long been using. With increased land sales there were fewer and fewer places where the Wampanoag could be assured of remaining on their land. By 1720, alarmed by the rate at which the Wampanoag were being displaced, London-based philanthropists bought the rights to Gay Head (now Aquinnah) and established it as a reservation for the tribe.

This conflict continued through the 19th century, as white landowners bought up the lands of impoverished Wampanoag individuals, or accepted them as payment for debts. Sometimes, the takings were more subtle. In 1854, for example, Jemima Easton petitioned the Massachusetts Senate and House of Representatives, stating “…that she herself is pure Indian, that she has occupied land held by her fathers for hundreds of years, but that the neighboring Whites have been gradually encroaching on this property until they have appropriated a great part of it to their own use and thus depriving her in a great degree of her means of subsistence.”

Although the Wampanoag continue to live in all parts of Martha’s Vineyard, the only tribal-owned land remaining is a small area in Aquinnah.

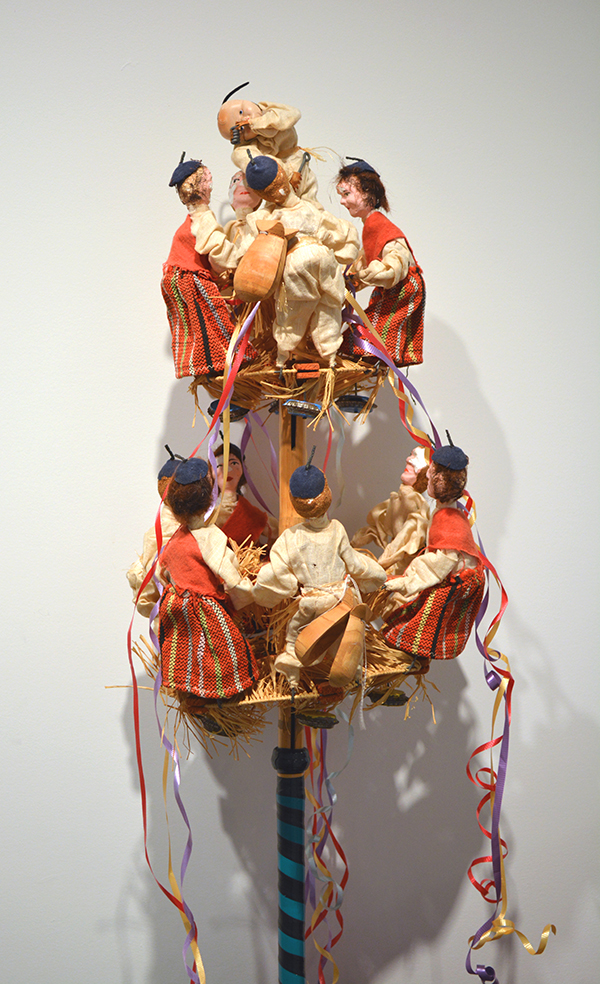

2. Enslavement on Martha’s Vineyard

Title: Bill of Sale of a Ten-Year-Old Black Child

Date: 1727

Reference: RU349

Massachusetts recognized slavery as legal in 1641, the year that English colonization of Martha’s Vineyard began, and Vineyarders profited from the enslavement of Africans both directly and indirectly. Zacccheus Mayhew, a selectman, judge, and great-great-grandson of the man who led the colonization of the Island, was one of eight Vineyarders known to have enslaved others.

Peter, the ten-year-old boy whose sale is recorded in this tattered document may have been born on the Island, the child of an enslaved woman, or taken from his mother and brought here independently. All we know about him is that he was enslaved by Zachheus Mayhew of Chilmark and that, in 1727, Mayhew sold him for £150 to Ebenezer Hatch of Falmouth. After this, Peter disappears from records, and from history. We do not know how long he lived, or where he died. This scrap of paper is the only evidence that he even existed.

Some of the earliest Vineyarders of African descent came, as Peter did, enslaved. Others, like the descendants of Cuffe Slocum of New Bedford, came as freemen, seeking opportunity. Still others, like Methodist lay preacher John Saunders, arrived on the Island after freeing themselves from enslavement. The Black history of Martha’s Vineyard began centuries before its emergence, around 1900, as a summer resort for successful African American families.

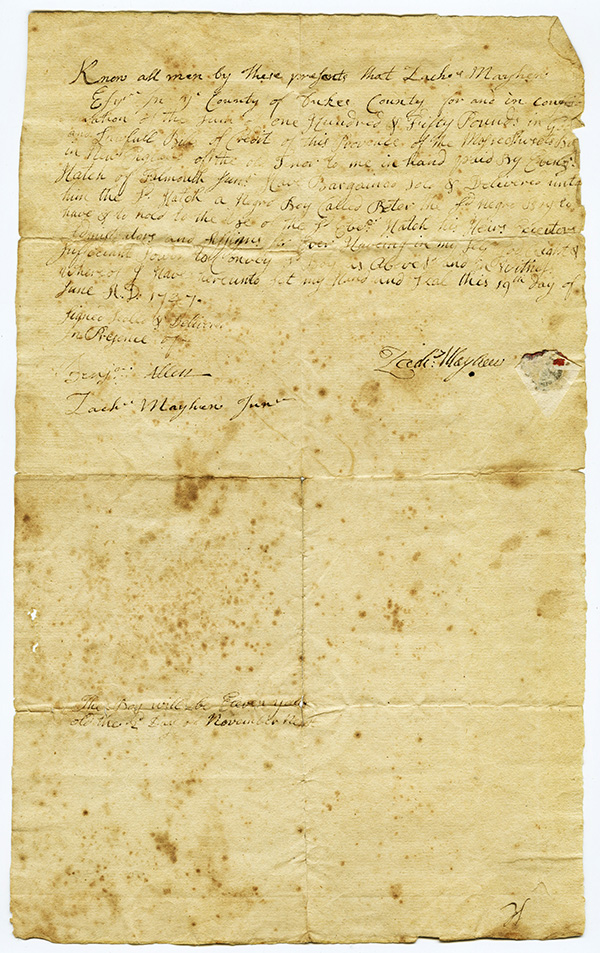

3. Keeping traditions in a new land

Title: Dancing Dolls (Brinquinho)

Date: c. 1900-1950

Reference: 2017.023.001

The first Portuguese immigrants to the Vineyard arrived, in ones and twos, before the Revolution. Over the next century the trickle became a stream and, by the 1880s, a torrent. Some came to the Vineyard directly, as crew members on whalers and cargo ships; others, having come seeking work in mainland textile mills, found a life of farming and inshore fishing on the Vineyard comfortingly familiar.

The children of immigrant farmers, sailors, and laborers became shopkeepers and fire chiefs, real estate brokers, and dentists. They assimilated but carried on traditions brought from the old country: foods, festivals, and music. Mary Paiva Drouin (1922-2006), the daughter of a first-generation Portuguese immigrant family, recalls how her family’s cherished “dancing dolls” in traditional Portuguese dress were paraded through the streets of Oak Bluffs during the Holy Ghost Festival and while caroling in Portuguese neighborhoods on Christmas Eve:

Frankie played the violin, my brother, Louis, played the guitar, and John played the guitar, and, of course, I had my dancing dolls that they brought from Portugal…We’d sing the song, we call it ”Abra la Porta”, it means “Open the Door,” in Portuguese… ‘Please would you open the door? We want to bring you greetings from the baby Jesus”…

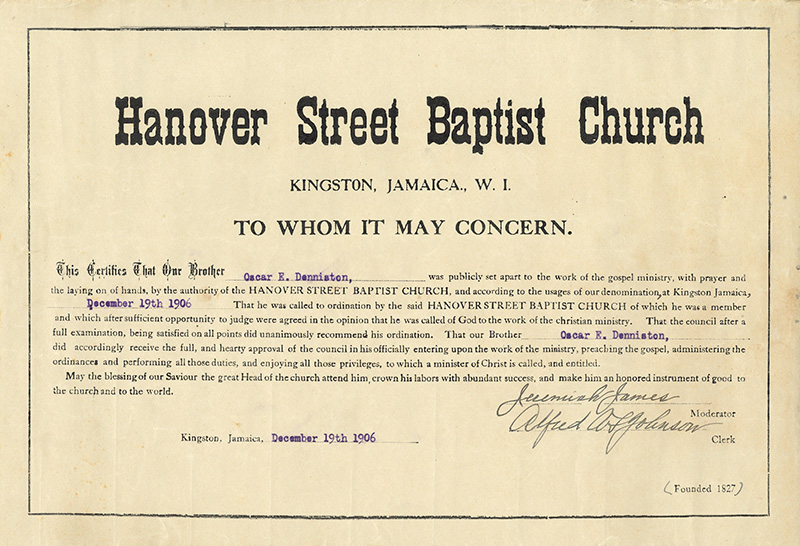

4. A church to welcome everyone

Title: Certificate of Ordination

Date: 1906

Reference: 2008.026

In 1901, Oscar E. Denniston of Kingston, Jamaica, came to Martha’s Vineyard to work with Madison Edwards at the Seamen’s Bethel in Vineyard Haven. Soon after, he began working with Susan Bradley at the Oakland Mission. Together they created a place for African Americans, Portuguese and Cape Verdean immigrants to attend religious services, receive instruction in English and basic arithmetic, and learn what they needed to pass the citizenship test.

Denniston returned to Jamaica after the death of his wife, Charlotte, in 1905. While there, he was ordained at the Hanover Street Baptist Church in Kingston. He remarried in 1907 and returned to Martha’s Vineyard with his new wife, Medora, and his two sons from his first marriage. When Susan Bradley died in 1908, Rev. Denniston took over the Oakland Mission and renamed it in her honor. Though parishioners were of all ethnic backgrounds, the Bradley Memorial Church continued to cater primarily to communities on the margins of Vineyard society: Portuguese, Cape Verdean, Wampanoag and African-American. In an era when racial and ethnic prejudice, and informal segregation, was routine on the Island, Bradley Memorial Church was an oasis for Vineyarders of color.

Reverend Denniston provided Sunday morning services, followed by Sunday school, and held Sunday evening services to accommodate black servants and other service-economy workers who were not free during the day. After his death in 1942, the Bradley Memorial Church ministered to a dwindling congregation for another twenty-four years before disbanding in 1966.

5. Growing businesses from scratch

Title: Shirt

Date: c.1980s

Reference: 2022.015.001

Between 1880 to 1924, when the restrictive Johnson-Reed Act greatly curtailed the number of immigrants allowed into the United States, more than 2.5 million Jews left their homes abroad to settle in America. Most came from eastern and southern areas of Europe, especially the former Russian Empire, including present-day Russia, Lithuania, Poland, and Ukraine. In addition to traditional drivers of emigration, such as war and declining agrarian economies, Jews carried the extra burdens of discrimination and oppression from governments and neighbors. As pogroms occurred across eastern Europe, the shadow of violence from their non-Jewish neighbors was a constant worry.

Judal Brickman was part of this diaspora. Born in present-day Lithuania in 1885, he moved to Denmark as a young man, but by 1911 he had decided to move to New York with his wife, Eudice, and their two children. Hearing of the need for a cobbler on Martha’s Vineyard he relocated his family once again in 1913. One of the earliest Jewish families to settle here, the Brickmans operated a shoe business on Main Street in Vineyard Haven that became Brickman’s department store. When his daughter Ida — chief buyer for Brickman’s — married David Levine, Brickman bought the storefront that became Vineyard Dry Goods and gave it to her, saying “go and make a million.”

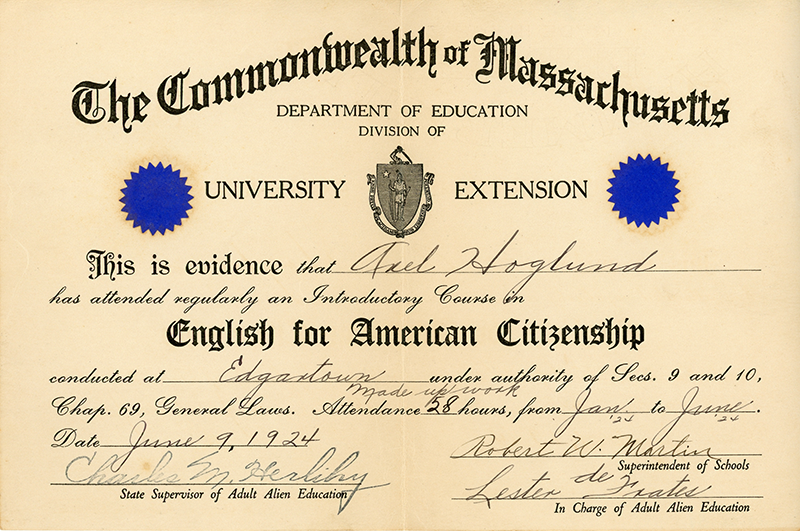

6. From northern Europe to a small Island

Title: Certificate of Completion, English Class of Johan Axel Hoglund

Date: 1924

Reference: RU610

The Johnson-Reed Act of 1924 tightened immigration restrictions, and adjusted country-by-country quotas, but not uniformly. Immigration from Asia was prohibited entirely, and the provisions of the act increased opportunities for would-be immigrants from northern and western Europe while tightening restrictions on those from southern and eastern Europe.

Johan Axel Hoglund, born in northern Sweden in 1901, was one beneficiary of the new policy. At 23, having completed his mandatory service in the Swedish army, Hoglund boarded a ship for America, his immigration sponsored by an uncle who already lived in Edgartown. Hoglund carried his clothes, his prized violin (he was a gifted amateur musician who, according to his family, could play a song after hearing it only once), and the sheaf of papers that he would be required to present to U. S. authorities, including a “certificate of good character” signed by the pastor of his church in Sweden. Once in America, he added the certificate shown here to his portfolio.

When he arrived on the Vineyard, Hoglund worked briefly with his uncle as a gardener before starting a successful house-painting business in Edgartown and expanding into interior decorating. He became friendly with the Cronig family — Jewish immigrants from Lithuania, who had come to America via Sweden — and married Annie Correia, herself the daughter of Portuguese immigrants. Known for his love of music, his 40 years of service to the Edgartown Fire Department, and the many times he painted the Old Whaling Church as a volunteer, Axel Hoglund died in 1981. His great-granddaughter donated his immigration papers to the Museum.

7. They have always been here

Title: Dial telephone Service Comes to Aquinnah

Date: 1955

Reference: RU465

From the beginnings of English colonization in the 1640s, the Wampanoag were pressured to abandon ways of life they had practiced for thousands of years and adopt European ways of life instead. The process reached a climax in 1870 when, under heavy pressure from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, the Wampanoag residents of Gay Head (now Aquinnah) narrowly voted to give up their reservation status and join the Commonwealth as citizens of the newly incorporated Town of Gay Head. Only by embracing “modern” (that is, European) ways of life, state officials argued, could Indigenous peoples succeed.

The incorporation of Gay Head, which included the division of the tribe’s jointly held “common lands” into individual lots with individual owners, accelerated the erosion of traditional Wampanoag culture, but did not — as state officials hoped — erase it completely. Traditional Wampanoag ways coexisted, as they had since First Contact, with European ones. This photograph, staged in May 1955 to celebrate the introduction of dial telephone service in Chilmark and Gay Head, captures the tension between tradition and modernity. Gay Head selectmen Leonard Vanderhoop and Edmond Cooper, in European-style business suits, participate in a ceremonial “first call” with their Chilmark counterparts while tribal chief Donald Malonson and medicine man Napoleon Madison, in traditional dress, look on.

To white onlookers, Malonson’s and Madison’s regalia was a quaint relic of the past. To the Aquinnah Wampanoag, it was part of an unbroken cultural tradition reaching thousands of years into the past. On the strength of that tradition, they fought for, and won, federal recognition for the tribe in 1987.

8. The newest immigrants

Title: Gislaine

Artist: Mila Lowe

Date: 2016

Reference: 2019.026.015

The story of immigration to the Vineyard is still being written, by newcomers from Asia, Eastern Europe, the Caribbean, and Brazil. In 2017, the Museum exhibited photographer Mila Lowe’s “Local Immigrants Project.” A Moldovan immigrant herself, Lowe undertook the project to document the wide diversity of recent immigrants to the Island. She wrote:

“Immigration is not a concept that is unfamiliar to this region, and many generations of newcomers found themselves on the shore of the Vineyard over the centuries. Each person’s story has the ability to make a profound contribution to the Island’s community. Through accepting our differences while in pursuit of harmony, we can promote tolerance and openness. The ongoing exchange of stories and values is what has shaped the historical process of cultural evolution.“

One of her subjects is Gislaine. When interviewed for the project, Gislaine emphasized her fondness for the English language and for this place:

“I was an English Teacher in Brazil…I always loved the English language and the American way of speaking it…English is a language that so many people speak around the world, and it’s so universal in a way. I think the Vineyard is very inviting. We have so many people from different countries here that I think everybody who gets here can find themselves.“