100 Years, 100 Stories – January

100 Years, 100 Stories

January: Artists of this Island

Made to tell stories, as symbols of prestige, or for sheer visual pleasure, works of art offer an avenue to understanding that books and documents do not. Artists on Martha’s Vineyard, whether they worked long ago or are working here now, put their creativity into objects that represent this Island and its people across cultural and economic boundaries to create a multi-faceted impression of this place.

1. A Wampanoag artist weaves together the past and the present

Title: Woven Bag

Artist: Linda Coombs

Date: 2011

Reference: 2018.007

Because of the distance in time and the ephemeral nature of many of the materials used in Wampanoag art of the past, it can be challenging to imagine the color and texture of the earliest works of art made on this Island. Contemporary Wampanoag artists and artisans help us picture the world of their ancestors, the first inhabitants of this Island, by making objects using old and new materials while drawing on old and new techniques.

Sometimes, as in this example, the aim is to faithfully recreate the work of the past. Aquinnah Wampanoag Linda Coombs has decades of experience teaching about the lives and culture of the Wampanoag people. She based this finger-woven bag on pieces from the 17th century and made it using the materials and techniques of her ancestors.

2. A girl demonstrates her domestic skills by stitching a sampler

Title: Sampler

Artist: Mary H. Norton

Date: 1823

Reference: 2018.020.001

Sewing was a necessary part of everyday life for women in an era when textiles were expensive household goods – most often used and repurposed until worn out. But embroidery went beyond necessity. It added beauty to everyday objects, whether as simple, elegant initials to identify a bedsheet, or as pure ornament on a wallet or waistcoat.

For families who could afford more than basic public education for their girl children in the first half of the 19th century, a demonstration of achievement in the domestic art of embroidery was an important milestone. Usually made when a girl was between the ages of 8 and 12, a sampler proved that she had learned this skill. Samplers could be simple cross-stitched alphabets or elaborate compositions of buildings, landscapes, and verses made using a variety of embroidery stitches. A source of family pride, they were often framed and placed on the parlor wall.

Mary H. Norton made this sampler in Holmes Hole (now Vineyard Haven) when she was around 12 years old. It resembles other samplers in the Museum’s collection enough to make it clear that there was probably a school or teacher training girls here on the Island at that time, but that school and teacher have not yet been identified. Born in Holmes Hole, she married Charles Cottle of Tisbury seven years after she stitched her sampler and moved with him to Scituate in the late 1850s.

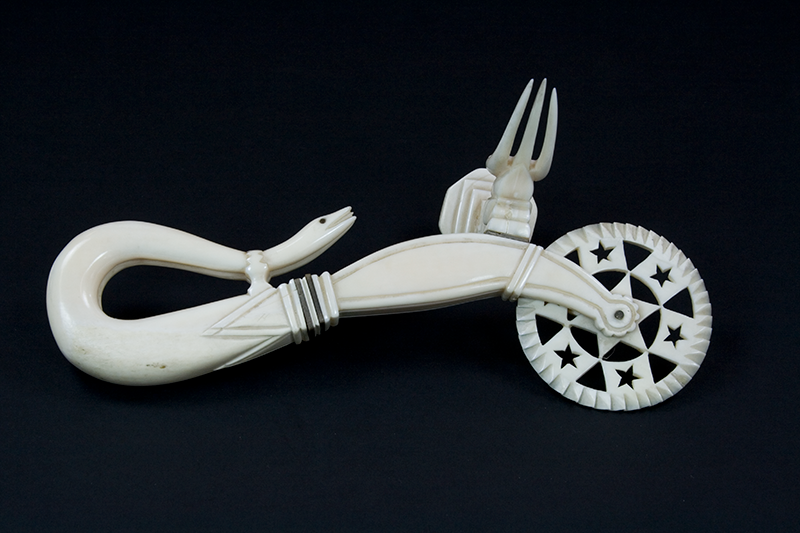

3. A whaleman fashions a multi-function tool from remains of the hunt

Title: Jagging Wheel

Artist: Unknown maker

Date: Mid-19th Century

Reference: Z1439

The primary products of the whale hunt were high-quality oil for fueling lamps and lubricating machinery, and baleen, which was used in corsets and umbrellas, but much of what remains from that enormously profitable 19th-century industry are objects made from what was left over after the whale oil had been rendered and shipboard work was finished. Seamen used the unsalable parts of whales and walruses – teeth, bones, and remnants of baleen – to create scrimshaw for their own amusement, as souvenirs, and as gifts to loved ones.

Though most familiar in the form of whales’ teeth carved with pictures of ships, scrimshaw was an extremely varied art. The Museum has hundreds of pieces in its collection, from large, complex swifts (yarn winders) to tiny sewing tools. The anonymous maker of this jagging wheel fashioned a multi-tool for pie making that combines three pieces of ivory into a fanciful gadget that can crimp pie crusts, make holes in the top crust for steam to escape, and create decorative patterns in the crusts as well.

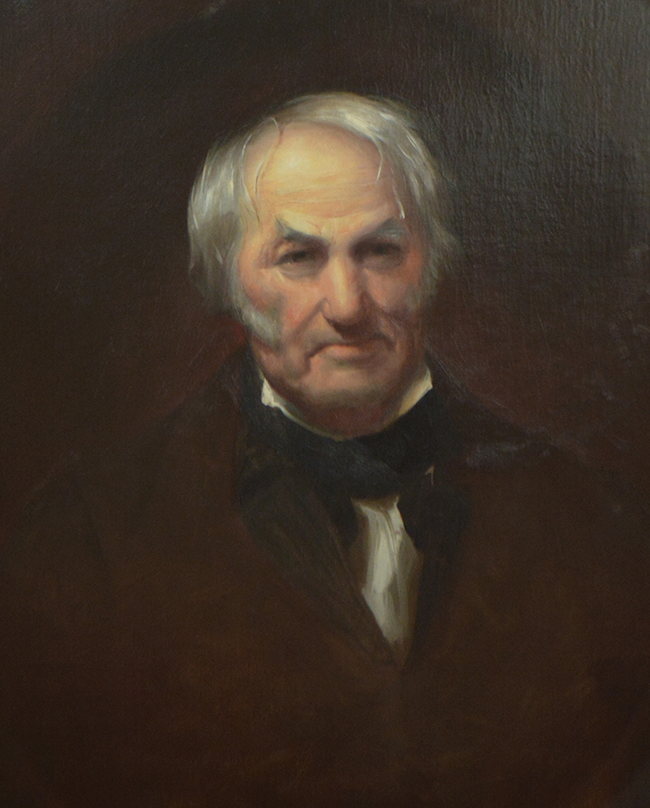

4. A wealthy businessman commissions a young portraitist

Title: Ichabod Norton

Artist: Edward Dalton Marchant

Date: c. 1830

Reference: 2013.012.001

Having one’s portrait painted has long been a mark of wealth and status. On Martha’s Vineyard in the 19th century, there were many successful merchants and sea captains who could afford to commission portraits of themselves and their families, but not enough to keep a painter in business. This is probably why the two best-known portrait artists from the Island, Frederick Mayhew and Edward Dalton Marchant, moved away as young men. Mayhew seems to have given up painting altogether, but Marchant went on to have a long and successful career as an artist.

This portrait shows Ichabod Norton, a wealthy Edgartown landowner and businessman. He probably commissioned Marchant to paint him around 1830, when Norton was around 70 years old and Marchant was still a young man, before he moved to New York and then Philadelphia, big cities where a portraitist was more likely to find wealthy sitters.

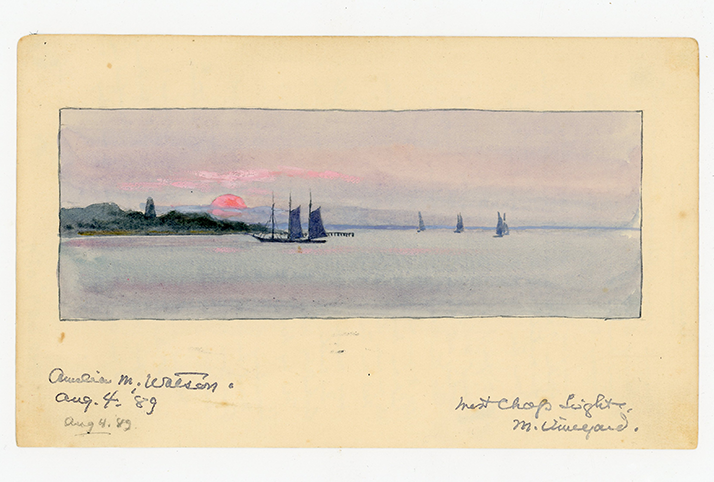

5. A watercolorist spends her summers teaching teachers

Title: West Chop Light

Artist: Amelia Watson

Date: 1889

Reference: 1942.059.007

Every summer from 1878 to 1907, the Martha’s Vineyard Summer Institute at Cottage City (now Oak Bluffs) held classes at a “vacation school” for actively employed teachers. Classes were offered in academic fields, teaching methods, and the arts.

Amelia Watson was one of the accomplished artists who came to teach at the Institute for many years. She lived in Connecticut, but traveled extensively to paint, lecture, and teach. This watercolor of West Chop Light at sunset is just one of many of Watson’s delicate drawings and watercolor sketches in the Museum’s collection. She made them on her day trips with students all over the Island and, in addition to their value as works of art, they record the nature of the Vineyard as it was in the 1880s.

6. A painter plans his work

Title: Study

Artist: Stanley Murphy

Date: 1978

Reference: 2008.003.223

Often forgotten when looking at a work of art is the body of knowledge, skill, and practice that came before. This occurs in a broad context– the artist may have studied, either formally or informally; and a narrow context – an individual work may be the result of planning and experimentation. In both cases, the process is equally invisible in the finished work. The Museum is fortunate to have an extensive collection of materials created by Stanley Murphy in its collection. These archives, sketches, studies, partially completed works, and finished works offer more than a glimpse into the process of this painter who integrated himself so thoroughly into the life of this Island.

Murphy spent many hours developing, learning, and experimenting with media and style over his decades-long career on Martha’s Vineyard, which began when he moved here with his young family in 1948. This study for a painting of one of the stone walls so emblematic of the up-Island landscape lays out ideas for composition, color ideas, and lighting notes.

7. A blind woman paints memory and abstraction

Title: Chappy

Artist: Mary Drake Coles

Date: c. 1985-1995

Reference: 2001.065

Mary Drake Coles learned to paint through formal and informal training and practice during childhood summers on Martha’s Vineyard, in her teens in Provincetown, and later at Smith College, in Paris, Majorca, Haiti, and New York. On the Vineyard, she knew the work of the abstract artist Vaclav Vytlacil. In Paris, she absorbed ideas from the modernists. All the while she was going blind.

In 1957, after glaucoma had finally taken Mary Drake Coles’s vision away, she moved from New York City to Edgartown because, as she later told the Museum’s oral history curator, Linsey Lee, “I knew it as a child. I remembered it.” Coles’s memory served her well, not only in navigating the streets of Edgartown with her guide dog, but in painting scenes she recalled from before her blindness was complete. As her vision deteriorated she planned her life so she could still make art. Her paints and other supplies were always arranged the same way. This arrangement, plus her memory, allowed her to continue working for the rest of her long life. She explained, “I cannot see what I’m doing. I can’t see a thing. I know what I have in mind when I’m doing it…instinctively, I know composition.”

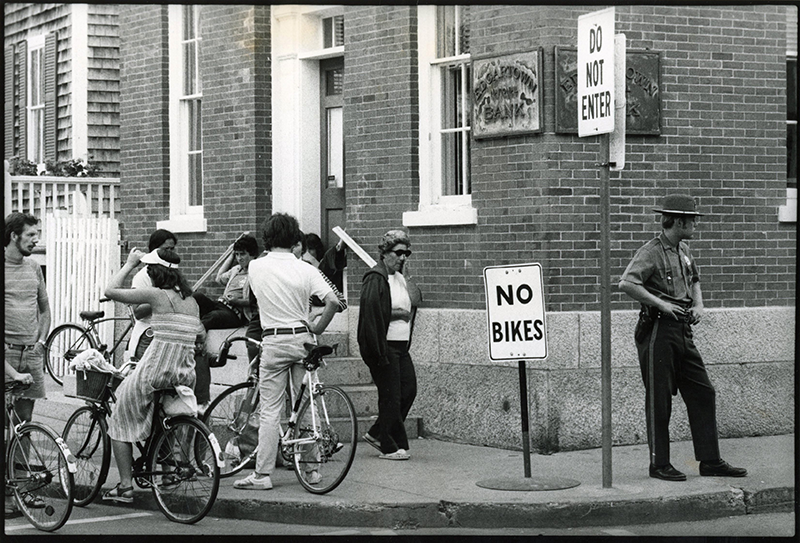

8. A photojournalist documents and shows stories

Title: No Bikes

Artist: Peter Simon

Date: c. 1985-1990

Reference: 2022.011

Peter Simon photographed rock and roll artists, antiwar demonstrations, people, and street scenes all over the country, but Martha’s Vineyard was the place he came home to, and images of the Island and its people formed a major part of his work.

As a photojournalist, Simon trained his camera on the dramatic and the mundane, making a record of the world around him and using his intimate knowledge of the Vineyard scene to make pictures that tell stories like this one:

At the corner of Main Street and South Water Street in Edgartown is a sight familiar to Vineyarders, year-round and seasonal alike, a group of tourists, who perhaps have just rented bicycles. They must discuss a change of plans, since peddling up Main Street past the police officer seems like it might not be the best idea.

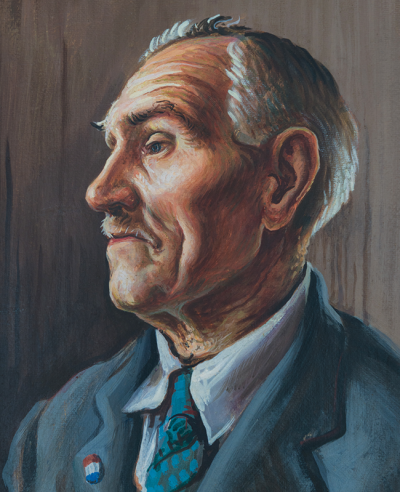

9. Two legends work together for an Island cause

Title: Zeb Tilton

Artist: Thomas Hart Benton

Date: 1941

Reference: 1976.002.001

The Cavalcade of 1941, a fair organized to benefit the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, brought together two Island celebrities – schooner captain and Vineyard native Zeb Tilton and renowned painter and seasonal Chilmark resident Thomas Hart Benton. Attendees paid a dime or a quarter to watch Benton paint Tilton for two hours on that August day more than 80 years ago, and this is the portrait they saw being made.

Benton was part of the Regionalist movement in American art and is most often associated with the midwest, but he found inspiration on Martha’s Vineyard from his first visits to the Island in the 1920s until his death in 1975. He painted many scenes of the land, the sea, and the people of this place.

Zeb Tilton (1868-1952) was a schooner captain who carried cargo between ports along the southern New England coast for 60 years. In his youth, the coastal schooner trade had been a thriving enterprise, evidenced by photographs of Vineyard Haven Harbor showing dozens of schooners at anchor, but by the time Benton painted this portrait steamships, trains, and trucks had rendered it obsolete. Zeb was the last of his kind and when he retired the year after Benton painted his portrait, an era came to a close.