100 Years, 100 Stories – June

100 Years, 100 Stories

June: Building on Sand

The land that the Wampanoag call Noepe and English colonists called Martha’s Vineyard was bulldozed into place 20,000 years ago by the glaciers of the last great ice age. The melting of those glaciers, and the steady rise in sea level that followed, transformed it into an island 5-6,000 years ago. The sea has been nibbling and gnawing at the margins of the Island ever since; longshore currents, waves, and storm tides constantly reshape its shorelines, cliffs, and coastal plains. The Wampanoag lived lightly on the land, but English traditions of individual land ownership and large, permanent coastal settlements set them at odds with the natural processes shaping the Island. Four hundred years later, Vineyarders are still seeking a workable middle ground.

1. A wedge of sand and gravel

Artist: Nathaniel Southgate Shaler

Date: 1888

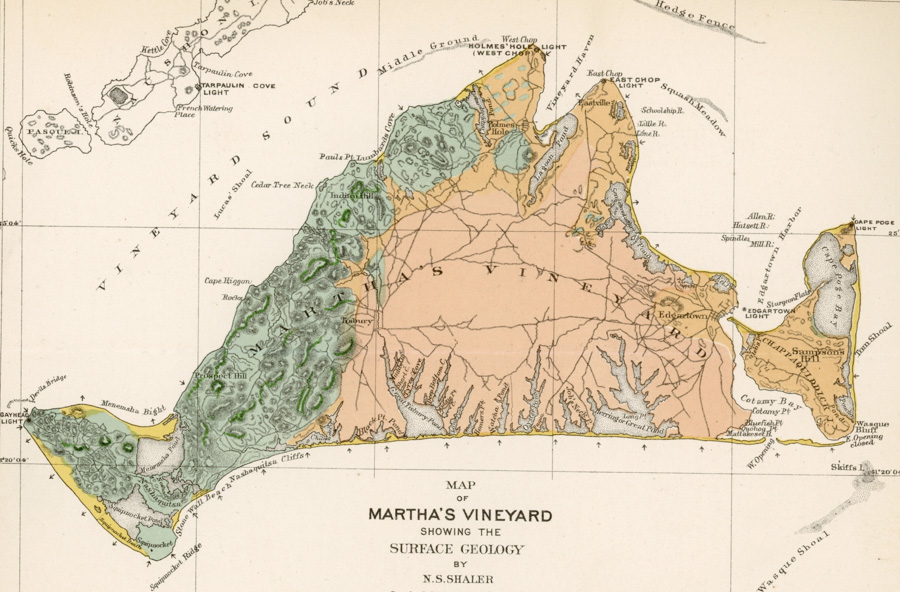

Beginning 75,000 years ago, miles-thick glaciers covered eastern North America in an ice age lasting 50,000 years: ten times longer than all of recorded human history. About 20,000 years ago, temperatures began to rise and the glaciers began to retreat northward again. New England’s southern coastline and outer islands, from Gravesend Bay at the western tip of Long Island to Provincetown at the northern tip of Cape Cod, mark the furthest extent of the glaciers’ advance.

The glaciers’ retreat left behind a “terminal moraine:” a long, loose ridge of sand, gravel, clay, and rocks similar, on a grand scale, to the line of dust left when a broom is swept across a smooth floor and then pulled back. Water from the melting glaciers percolates through the moraine, washing away sand, silt, and other lightweight sediment and spreading them across a broad, flat “outwash plain” to the south.

This map of the Island shows the landscape that the glaciers made. The cliffs of the north shore and the uplands of Aquinnah, Chilmark, West Tisbury, Oak Bluffs, and Chappaquiddick are parts of the terminal moraine. The flat, sandy center of the Island, stretching from the Lagoon and Sengekontacket Pond toward South Beach, is an outwash plain.

2. A lost pond and a vanished creek

Artist: Joseph F. W. Des Barres for the Royal Navy

Date: 1781

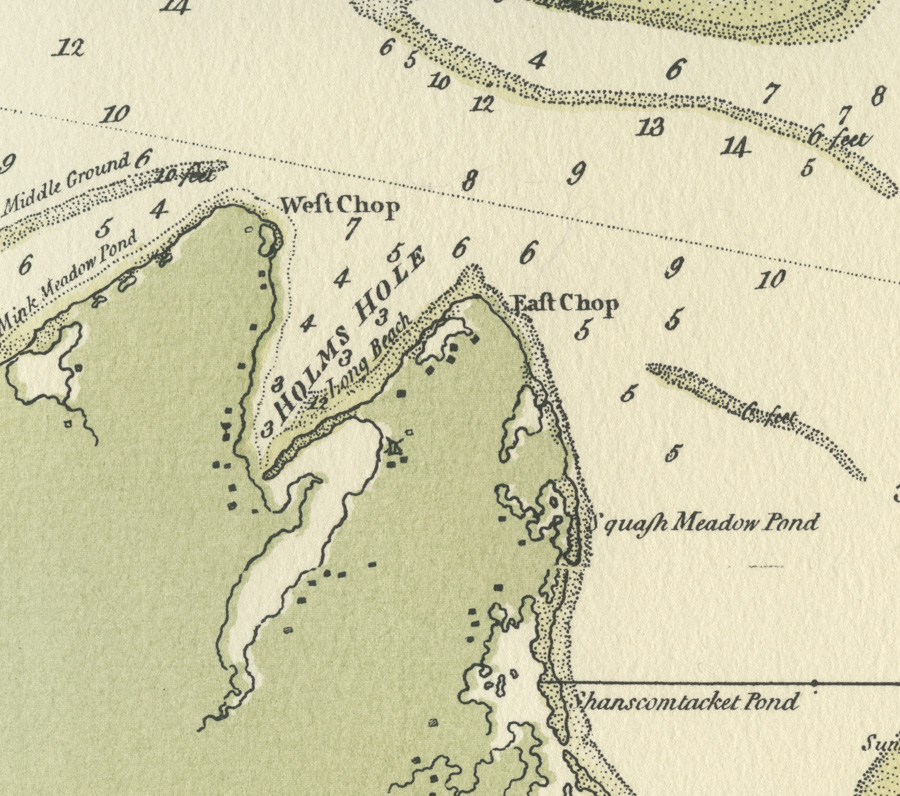

Lieutenant Joseph F. W. Des Barres (“de Bar”), an officer in the Royal Navy, mapped the coast of eastern North America during the American Revolution. His charts, issued in a multi-volume atlas called The American Neptune, remained the best available for nearly 75 years. Today, they are invaluable historical sources: detailed portraits of the Vineyard as it looked before the shoreline changes of the last 250 years.

This view of Holmes Hole (now Vineyard Haven) harbor in 1781 looks familiar at first glance, but a closer look reveals unfamiliar features. Point Pond, just inside the tip of West Chop, was once a refuge for small fishing boats. It disappeared shortly after 1900 when waves and currents erased the narrow strip of beach dividing it from the harbor. The opening that, spanned by a drawbridge, now connects Lagoon Pond with the harbor did not exist in Des Barres’ time. Instead, boats and small ships entered the Lagoon through Bass Creek: A broad channel, 6-7 feet deep, at the head of the harbor. It, too, is gone today: Water Street and Lagoon Pond Road follow the path it once took.

Des Barres’ chart shows the Middleground, a narrow shoal off the north shore of West Chop, lying about two feet below the surface — shallower than it is today. If it was even shallower earlier in the 1700s, and perhaps once an exposed Island, legends that Colonial-era farmers grazed their sheep there may be true.

3. The schooner under Five Corners

Title: The Harbor of Holmes Hole

Artist: Henry L. Whiting for the US Coast Survey

Date: 1875-1885

The hurricane that struck Martha’s Vineyard in 1815 cut a channel through the barrier beach that divided Lagoon Pond from Holmes Hole (now Vineyard Haven) Harbor. The existence of a second channel changed the currents that flowed between the two bodies of water. Over the next 20 years, the new channel grew wider and deeper, and Bass Creek — the old channel — grew shallower, and so less useful.

In 1835, the citizens of Holmes Hole blocked Bass Creek by loading a worn-out schooner with rocks and sinking it at the foot of Beach Street, where the Five Corners intersection is today. The section of Bass Creek north of the sunken schooner was filled with sand and gravel, and Water Street was built on top of it. Union Wharf, where the Steamship Authority ferries dock today, was built a few years later at the corner of Water and Union Streets. The closing of Bass Creek made it possible to extend Beach Street along the barrier beach toward the 1815 channel, making it possible to establish shipyards and other businesses there.

This chart, drawn by Henry L. Whiting for the US Coast Survey in 1847, shows the new entrance channel to the Lagoon and the closure of Bass Creek. It also shows Union Wharf, and the newly built Bradley and Yale Marine Railway (a forerunner of the Martha’s Vineyard Shipyard) on Beach Road.

4. Sea spray on the rails

Date: c. 1890

Reference: RU 465 A18 14b

The Martha’s Vineyard Railroad operated from 1872 to 1896, carrying passengers and their baggage from the steamer wharf in Oak Bluffs to a depot on the outskirts of Edgartown and then to the Mattakesett Lodge hotel at Katama. The railroad’s backers elected to lay the track from Oak Bluffs to Edgartown atop the barrier beach between Sengekontacket Pond and Nantucket Sound.

The beachfront route was shorter than the inland route along the back of Sengekontacket would have been, and so reduced the railroad’s initial construction costs. It also gave passengers a taste of salt air and expansive views of the pond and ocean, both of which contributed to the railroad’s popularity. These benefits, however, came at a price. Barrier beaches are naturally unstable, shifting as sand eroded on the ocean side is deposited on the bay side. Waves from winter storms routinely washed over the tracks, uprooting them or burying them in the sand.

The need to repair the tracks every spring before summer operations began placed a significant financial burden on the railroad, which only operated for 10 weeks each year. Unable to turn a consistent profit, the company went bankrupt in 1896. The locomotive was sold and shipped off-Island, the depot demolished, and the rails torn up and sold for scrap.

5a. Once a wetland

Date: 1938

Reference: RU 465 A25 18c

5b. Once a wetland

Photographer: Katharine P. Van Riper

Date: 2021

Reference: 2022.004.002.017

The Five Corners intersection at the center of Vineyard Haven was, until 1835, a water-filled channel. So was Water Street, which runs north from Five Corners toward the harbor and the Steamship Authority terminal. Lagoon Pond Road, which runs south toward the Museum, runs past a former wetland that was filled in the 1950s to create Veterans’ Park. Beach Road, which runs northeast toward the Martha’s Vineyard Hospital, is built on a former barrier beach only a foot or two above sea level. The land between Beach Road and Lagoon Pond Road was, until the late 1930s, water.

Five Corners and the surrounding roads are, as a result, prone to flooding in heavy rains, high tides, and storms. Extensive paving, and the replacement of wetlands by solid fill that can support buildings, limits the ability of water to drain away. The first photograph, looking down Beach Road toward Five Corners, was taken during the 1938 Hurricane. The second photograph, looking across Five Corners from Water Street toward Beach Road, was taken during the October 2021 northeaster.

Rising sea levels and intensifying storms — effects of global climate change — are likely to make flooding at Five Corners more frequent and more severe, cutting off direct access to the hospital, and potentially limiting the usability of the Island’s only year-round freight port.

6. The wreckage of an era

Date: 1944

Reference: RU 465 A16 39d

“Permanent” structures built on unstable shorelines will, if nothing is done to protect them, eventually be destroyed by the sea. The ground beneath them can be washed away, causing them to collapse; they can be flooded or swept out to sea by storm tides; or they can simply be battered apart by waves that reach up onto the shore. Destruction, or serious damage, is a matter of “when,” not “if.” The question is how much use the owner(s) can get from it before it is destroyed, or extreme measures become necessary to protect it.

The businessmen who developed Oak Bluffs as a summer resort in the 1860s and 1870s arranged for its waterfront to be lined with bathhouses. Long, narrow buildings set on pilings above the sand, they stretched — three rows deep — from the steamer wharf to the far corner of Ocean Park. Divided into individual cubicles with doors, they served as changing rooms and gave beachgoers a place to store their street clothes while they splashed in the water and their bathing suits when they were done.

The bathhouses remained a fixture of Oak Bluffs — a monument to the social customs of a bygone era — until September 14, 1944, when what became known as the Great Atlantic Hurricane struck the Island. In a single night, the beachfront was wiped clean. The remains of the bathhouses, reduced to kindling, were washed out to sea and (as shown in this photo) or piled onto the steamer wharf by the waves.

7. Bunker in the surf

Date: c. 1960-1970s

Reference: 2019.004.042.019

The southern edge of Martha’s Vineyard, from Chilmark Pond to Wasque Point, is a nearly unbroken strip of barrier beach dividing the southern edges of the Great Ponds from the Atlantic. South Beach, though it appears stable and unchanging to casual observers, is in constant motion: steadily migrating northward due to erosion and winter storm waves washing over it.

The concrete structure shown here was built by the US Navy at Katama — the Edgartown end of South Beach — during World War II. Part of an installation used to train naval aviators in aerial gunnery, it originally stood in the dunes behind the beach, facing inland. By the late 1960s or early 1970s, when this picture was taken, it stood at the water’s edge, with the waves breaking against its back wall. Small children played inside it at low tide, and teenagers jumped off its roof into the oncoming surf at high tide. The concrete structure was still where it had always been, but the beach had moved beneath it.

By the 1990s, the beach had migrated even further inland. The Bunker stood where it had for fifty years, but it was now underwater, well offshore. The beach continues to move north, its dunes covering the southern edges of the ponds behind it.

8. Back from the brink

Photographer: Tim Johnson

Date: 2015

Building lighthouses on the tops of high cliffs makes them visible, but also vulnerable. Storm waves regularly wash against the bases of the cliffs that line the northern shore of the Island, undercutting them and causing the cliff faces and the land above to slump onto the beach. Each of the four Island lighthouses built on a headland has been relocated at least once. Cape Poge, the most-often moved, has been shifted at least four times and possibly more, the last time (in 1987) by helicopter.

The brick tower of the current Gay Head Light was built in 1856. By the early twenty-first century, 150 years later, erosion had left it dangerously close to the edge of the cliffs. In June 2015, the lighthouse was relocated 129 feet further inland: an exacting process that involved adding temporary reinforcements to the brick tower, constructing a platform of steel beams beneath it, and laying a set of rails to the reinforced concrete pad at the new location. Inched along the rails by pneumatic pistons, the tower was lowered carefully into place on its new foundation, which was covered in dirt and plants saved from the original site.

Now 180 feet from the cliff face, the lighthouse is projected to be safe for another 150 years.